This, I would imagine, only happens to new immigrants to California. Though rare, natives will have grown up with them. (Please note that “though rare” can apply equally to California natives and earthquakes.) I had just turned 30 when I arrived in the Bay Area from the Boston suburbs. Within three weeks, I found a cheap, furnished apartment and a graveyard shift doing data entry for a small startup nearby.

I moved to California from a Boston suburb after my first visit, staying with my aunt and cousins in the Bay Area. I unexpectedly fell in love with the place. So much so that I pulled up stakes and moved back there a little over three months after I came home. And I’m not normally the kind of person who does radical things like that, giving up a newspaper job I had for over ten years and quite likely my media career. But after seeing California, I couldn’t face another New England winter.

Just a Little Bump?

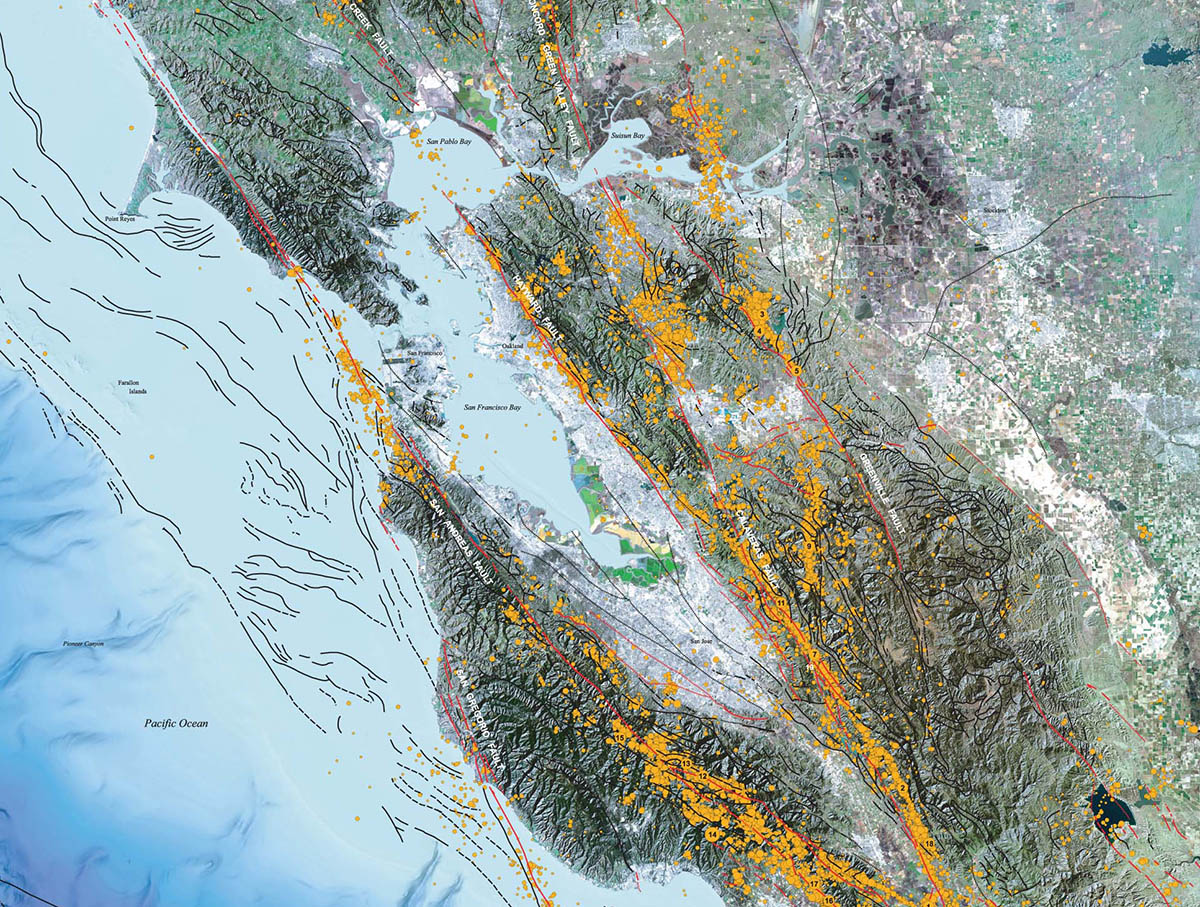

My aunt had mentioned earthquakes as part of life there. She told me they mostly felt like a heavy truck driving by if they were at all noticeable. That sounded quite reasonable. Even though the West Coast was known for its fault lines, news of seismic events there almost never made it to the East Coast. There was, in fact, a fault quite near to where my aunt lived, known for its frequent but very mild shaking.

I was settled into my new job and had adjusted to the odd hours, still feeling the joy of being somewhere I could go out in a light jacket in mid-December. A large window in my cheap apartment provided me with an astounding view of Mt. Diablo, three-quarters of a mile high, seven miles due east.

It was a beautiful mid-morning, not quite two months after I arrived, and I had finished my breakfast/dinner and was getting ready to go to bed when I felt something not like a truck driving by but rather one hitting the building. A big truck. It wasn’t even the rolling motion you sometimes hear described; these were sharp, hard-edged shakes. The tree outside my window looked like a giant, invisible hand was shaking it back and forth like it was made of rubber.

Whitecaps and Mad Laughter

Outside, I could hear the sound of surf, the contents of the swimming pool were being splashed out onto the surrounding patio. A few apartments down from me, I could hear a young screaming wildly. In the auto repair shop behind my bedroom window, a man was laughing madly. My brand-new little TV on its weak little table was walking around the living room. A corner of my apartment was bending in smooth S-curves as I watched.

The sound of an earthquake is impossible to describe. It is the sound of things shaking that are never supposed to shake; things that are far too big to shake. There is some sense of the motion becoming sound in frequencies so low they felt as much as heard. Of course, there was the sharp rattle of dinnerware in cabinets and silverware in drawers. That has always had the same impact on me as the screeching violins in the shower scene in Psycho. Luckily, things moved, but nothing fell and broke.

It’s also hard to describe what was going on inside my head, aside from the panic, that is. The initial shock and surprise became a feeling of terror that sustained throughout the shaking. The onset was so sudden and the shaking so continuous, it was impossible to judge how long it was going to last or how much worse it may get. Earthquakes, I was to learn, were like that.

Finally, with the last few shudders, it stopped. It was quiet for a moment, then the guy in the garage laughed and shouted something like, “That was a good one!” A few moments after that, I heard the woman scream, “It’s going to come again!” She was right. Less than a minute later, there was another solid couple of bumps.

A New Reality

Sitting in my apartment afterward, I found myself facing a reality that had changed forever. The concept of “solid ground” ceased to exist for me. Ground could no longer be depended on to be solid. There was nowhere to run from one of these, nowhere to take cover. It was like a serpent suddenly leaping out at me in my newfound paradise. It didn’t make we want to go back, yet I was uncertain that I could ever adjust to a life with this kind of thing lurking unseen. I knew virtually nothing about earthquakes.

Geology was one of my favorite science topics in school, but I only really learned about the kind they had back there, glacial moraines, evaluating monoclines and anticlines from layers of exposed rock, and things like that. Those were things that took thousands or millions of years to change. It was inconceivable to me to have something happen in a matter of seconds. I knew it could. But being there when it did was something else entirely.

This event, on January 24, 1980, was a shallow, 5.6 quake with an epicenter about 15 miles away. There were numerous aftershocks, including one of 5.0 three days later. There was some damage and some injuries, but earthquakes of this size happen in the Diablo Valley and are considered “local news” at best. I learned later that how an earthquake felt at a given location was attributable to a number of factors, including the obvious like the distance to the epicenter and its depth, to the nature of the geological makeup of the earth between the epicenter and where one is.

For example, a while after this, I moved to a much nicer apartment not far from my first one, where there were a couple of quakes I should have felt, but didn’t. I discovered that it was on an outcropping of very hard bedrock.

On the other hand, I was living for a while with some people in a house to the south in Milpitas and one night I was nearly thrown out of bed by a short, but incredibly jarring earthquake. Its intensity was in the low 4’s, but it was centered along the Calaveras Fault just a few miles from the house. Curiously, I could see flashing outside when it was happening and thought it was probably power lines arcing. However, there were no power outages and, when I looked the next day, there were no power lines in the area. They were all underground. And them there was the storied Loma Prieta quake. When it occurred, I was living 14 miles to the north in West San Jose. But that’s another story.

A New Interest

Obviously, that first quake didn’t drive me back to Massachusetts. I adjusted to the fact that earthquakes were simply geology in the present tense. From that point on, however, I embarked on learning everything I could about earthquakes, tectonic plates, and the like.

Thirty years later I got to experience a longstanding dream and watched lava gushing into the Pacific from the Kilauea volcano, erupting once again as I write this and where I will be heading to for a brief vacation next week. It was no less remarkable seeing new land being created than it was to feel it shake. I knew I was watching something happing that would affect the earth for millions of years to come.

In the summer of 2024, I found myself walking through a narrow canyon in Iceland with the edge of the Eurasian Plate rising about ten feet to my left and the North-American Plate about thirty to my right. According to our guide, that rift is widening at a rate of about 20mm per year, breakneck speed in geological terms.

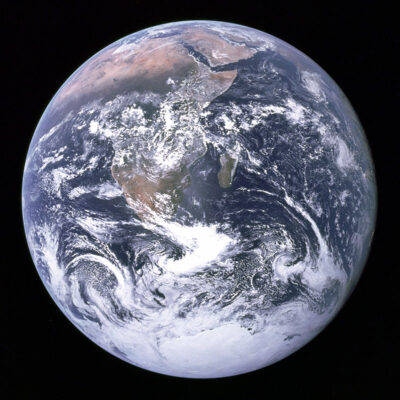

Like the Blue Marble

Now, many years later, I realize impact of experiencing that first earthquake was very similar of seeing the famed Blue Marble photo of the Earth, taken by an astronaut about Apollo 17 on its way to the moon. It put things for me into a very different perspective, one that inched me towards a better understanding of how things really are. Though it lacked the photo’s breathtaking beauty, it was a lesson of our fragility as a species and our tremendous good fortune of having this ground beneath our feet, whether it moves a little from time to time, or not.

Leave a Reply